The Provost Read online

Page 12

On going into the street, I met several persons running to the scene ofaction, and, among others, Mrs Beaufort, with a gallant of her own, andboth of them no in their sober senses. It's no for me to say who he was;but assuredly, had the woman no been doited with drink, she never wouldhave seen any likeness between him and me, for he was more than twentyyears my junior. However, onward we all ran to Mrs Fenton's house, wherethe riot, like a raging caldron boiling o'er, had overflowed into thestreet.

The moment I reached the door, I ran forward with my stick raised, butnot with any design of striking man, woman, or child, when a ramplordevil, the young laird of Swinton, who was one of the most outstrapolousrakes about the town, wrenched it out of my grip, and would have, I daresay, made no scruple of doing me some dreadful bodily harm, when suddenlyI found myself pulled out of the crowd by a powerful-handed woman, whocried, "Come, my love; love, come:" and who was this but that scarletstrumpet, Mrs Beaufort, who having lost her gallant in the crowd, andbeing, as I think, blind fou, had taken me for him, insisting before allpresent that I was her dear friend, and that she would die for me--withother siclike fantastical and randy ranting, which no queen in a tragedycould by any possibility surpass. At first I was confounded andovertaken, and could not speak; and the worst of all was, that, in amoment, the mob seemed to forget their quarrel, and to turn in derisionon me. What might have ensued it would not be easy to say; but just atthis very critical juncture, and while the drunken latheron was castingherself into antic shapes of distress, and flourishing with her hands andarms to the heavens at my imputed cruelty, two of the town-officers cameup, which gave me courage to act a decisive part; so I gave over to themMrs Beaufort, with all her airs, and, going myself to the guardhouse,brought a file of soldiers, and so quelled the riot. But from that nightI thought it prudent to eschew every allusion to Mrs Fenton, and tacitlyto forgive even Swinton for the treatment I had received from him, byseeming as if I had not noticed him, although I had singled him out byname.

Mrs Pawkie, on hearing what I had suffered from Mrs Beaufort, was veryzealous that I should punish her to the utmost rigour of the law, even todrumming her out of the town; but forbearance was my best policy, so Ionly persuaded my colleagues to order the players to decamp, and to givethe Tappit-hen notice, that it would be expedient for the future sale ofher pies and porter, at untimeous hours, and that she should flit herhowff from our town. Indeed, what pleasure would it have been to me tohave dealt unmercifully, either towards the one or the other? for surelythe gentle way of keeping up a proper respect for magistrates, and othersin authority, should ever be preferred; especially, as in cases likethis, where there had been no premeditated wrong. And I say this withthe greater sincerity; for in my secret conscience, when I think of theaffair at this distance of time, I am pricked not a little in reflectinghow I had previously crowed and triumphed over poor Mr Hickery, in thematter of his mortification at the time of Miss Peggy Dainty's falsestep.

CHAPTER XXXVII--THE DUEL

Heretofore all my magisterial undertakings and concerns had thriven in avery satisfactory manner. I was, to be sure, now and then, as I havenarrated, subjected to opposition, and squibs, and a jeer; and enviousand spiteful persons were not wanting in the world to call in question myintents and motives, representing my best endeavours for the public goodas but a right-handed method to secure my own interests. It would be avain thing of me to deny, that, at the beginning of my career, I wasmisled by the wily examples of the past times, who thought that, intaking on them to serve the community, they had a privilege to see thatthey were full-handed for what benefit they might do the public; but as Igathered experience, and saw the rising of the sharp-sighted spirit thatis now abroad among the affairs of men, I clearly discerned that it wouldbe more for the advantage of me and mine to act with a conformitythereto, than to seek, by any similar wiles or devices, an immediate andsicker advantage. I may therefore say, without a boast, that the two orthree years before my third provostry were as renowned and comfortable tomyself, upon the whole, as any reasonable man could look for. We cannot,however, expect a full cup and measure of the sweets of life, withoutsome adulteration of the sour and bitter; and it was my lot and fate toprove an experience of this truth, in a sudden and unaccountable fallingoff from all moral decorum in a person of my brother's only son, Richard,a lad that was a promise of great ability in his youth.

He was just between the tyning and the winning, as the saying is, whenthe playactors, before spoken off, came to the town, being then in hiseighteenth year. Naturally of a light-hearted and funny disposition, andpossessing a jocose turn for mimickry, he was a great favourite among hiscompanions, and getting in with the players, it seems drew up with thatlittle-worth, demure daffodel, Miss Scarborough, through theinstrumentality of whose condisciples and the randy Mrs Beaufort, thatriot at Widow Fenton's began, which ended in expurgating the town of thewhole gang, bag and baggage. Some there were, I shall here mention, whosaid that the expulsion of the players was owing to what I had heardanent the intromission of my nephew; but, in verity, I had not the leastspunk or spark of suspicion of what was going on between him and themiss, till one night, some time after, Richard and the young laird ofSwinton, with others of their comrades, forgathered, and came to highwords on the subject, the two being rivals, or rather, as was said,equally in esteem and favour with the lady.

Young Swinton was, to say the truth of him, a fine bold rattling lad,warm in the temper, and ready with the hand, and no man's foe so much ashis own; for he was a spoiled bairn, through the partiality of old LadyBodikins, his grandmother, who lived in the turreted house at the town-end, by whose indulgence he grew to be of a dressy and rakishinclination, and, like most youngsters of the kind, was vain of hisshames, the which cost Mr Pittle's session no little trouble. But--notto dwell on his faults--my nephew and he quarrelled, and nothing lesswould serve them than to fight a duel, which they did with pistols nextmorning; and Richard received from the laird's first shot a bullet in theleft arm, that disabled him in that member for life. He was left fordead on the green where they fought--Swinton and the two seconds making,as was supposed, their escape.

When Richard was found faint and bleeding by Tammy Tout, the town-herd,as he drove out the cows in the morning, the hobleshow is not to bedescribed; and my brother came to me, and insisted that I should give hima warrant to apprehend all concerned. I was grieved for my brother, andvery much distressed to think of what had happened to blithe Dicky, as Iwas wont to call my nephew when he was a laddie, and I would fain havegratified the spirit of revenge in myself; but I brought to mind hisroving and wanton pranks, and I counselled his father first to abide theupshot of the wound, representing to him, in the best manner I could,that it was but the quarrel of the young men, and that maybe his son wasas muckle in fault as Swinton.

My brother was, however, of a hasty temper, and upbraided me with myslackness, on account, as he tauntingly insinuated, of the young lairdbeing one of my best customers, which was a harsh and unrighteous doing;but it was not the severest trial which the accident occasioned to me;for the same night, at a late hour, a line was brought to me by a lassie,requesting I would come to a certain place--and when I went there, whowas it from but Swinton and the two other young lads that had been theseconds at the duel.

"Bailie," said the laird on behalf of himself and friends, "though youare the uncle of poor Dick, we have resolved to throw ourselves into yourhands, for we have not provided any money to enable us to flee thecountry; we only hope you will not deal overly harshly with us till hisfate is ascertained."

I was greatly disconcerted, and wist not what to say; for knowing therigour of our Scottish laws against duelling, I was wae to see threebrave youths, not yet come to years of discretion, standing in the periland jeopardy of an ignominious end, and that, too, for an injury done tomy own kin; and then I thought of my nephew and of my brother, that,maybe, would soon be in sorrow for the loss of his only son. In short, Iwas tried almost

beyond my humanity. The three poor lads, seeing mehesitate, were much moved, and one of them (Sandy Blackie) said, "I toldyou how it would be; it was even-down madness to throw ourselves into thelion's mouth." To this Swinton replied, "Mr Pawkie, we have castourselves on your mercy as a gentleman."

What could I say to this, but that I hoped they would find me one; andwithout speaking any more at that time--for indeed I could not, my heartbeat so fast--I bade them follow me, and taking them round by the backroad to my garden yett, I let them in, and conveyed them into a warehousewhere I kept my bales and boxes. Then slipping into the house, I tookout of the pantry a basket of bread and a cold leg of mutton, which, whenMrs Pawkie and the servant lassies missed in the morning, they could notdivine what had become of; and giving the same to them, with a bottle ofwine--for they were very hungry, having tasted nothing all day--I wentround to my brother's to see at the latest how Richard was. But such astang as I got on entering the house, when I heard his mother wailingthat he was dead, he having fainted away in getting the bullet extracted;and when I saw his father coming out of the room like a demented man, andheard again his upbraiding of me for having refused a warrant toapprehend the murderers--I was so stunned with the shock, and with thethought of the poor young lads in my mercy, that I could with difficultysupport myself along the passage into a room where there was a chair,into which I fell rather than threw myself. I had not, however, beenlong seated, when a joyful cry announced that Richard was recovering, andpresently he was in a manner free from pain; and the doctor assured methe wound was probably not mortal. I did not, however, linger long onhearing this; but hastening home, I took what money I had in myscrutoire, and going to the malefactors, said, "Lads, take thir twa threepounds, and quit the town as fast as ye can, for Richard is my nephew,and blood, ye ken, is thicker than water, and I may be tempted to giveyou up."

They started on their legs, and shaking me in a warm manner by both thehands, they hurried away without speaking, nor could I say more, as Iopened the back yett to let them out, than bid them take tent ofthemselves.

Mrs Pawkie was in a great consternation at my late absence, and when Iwent home she thought I was ill, I was so pale and flurried, and shewanted to send for the doctor, but I told her that when I was calmed, Iwould be better; however, I got no sleep that night. In the morning Iwent to see Richard, whom I found in a composed and rational state: heconfessed to his father that he was as muckle to blame as Swinton, andbegged and entreated us, if he should die, not to take any steps againstthe fugitives: my brother, however, was loth to make rash promises, andit was not till his son was out of danger that I had any ease of mind forthe part I had played. But when Richard was afterwards well enough to goabout, and the duellers had come out of their hidings, they told him whatI had done, by which the whole affair came to the public, and I got greatfame thereby, none being more proud to speak of it than poor Dickhimself, who, from that time, became the bosom friend of Swinton; in somuch that, when he was out of his time as a writer, and had gone throughhis courses at Edinburgh, the laird made him his man of business, and, ina manner, gave him a nest egg.

CHAPTER XXXVIII--AN INTERLOCUTOR

Upon a consideration of many things, it appears to me very strange, thatalmost the whole tot of our improvements became, in a manner, the parentsof new plagues and troubles to the magistrates. It might reasonably havebeen thought that the lamps in the streets would have been a terror toevil-doers, and the plainstone side-pavements paths of pleasantness tothem that do well; but, so far from this being the case, the very reversewas the consequence. The servant lasses went freely out (on theirerrands) at night, and at late hours, for their mistresses, without theprotection of lanterns, by which they were enabled to gallant in a waythat never could have before happened: for lanterns are kenspecklecommodities, and of course a check on every kind of gavaulling. Thus,out of the lamps sprung no little irregularity in the conduct ofservants, and much bitterness of spirit on that account to mistresses,especially to those who were of a particular turn, and who did not choosethat their maidens should spend their hours a-field, when they could beprofitably employed at home.

Of the plagues that were from the plainstones, I have given an exemplaryspecimen in the plea between old perjink Miss Peggy Dainty, and the widowFenton, that was commonly called the Tappit-hen. For the present, Ishall therefore confine myself in this _nota bena_ to an accident thathappened to Mrs Girdwood, the deacon of the coopers' wife--a mostmanaging, industrious, and indefatigable woman, that allowed no grass togrow in her path.

Mrs Girdwood had fee'd one Jeanie Tirlet, and soon after she came home,the mistress had her big summer washing at the public washing-house onthe green--all the best of her sheets and napery--both what had been usedin the course of the winter, and what was only washed to keep clear inthe colour, were in the boyne. It was one of the greatest doings of thekind that the mistress had in the whole course of the year, and the valueof things intrusted to Jeanie's care was not to be told, at least so saidMrs Girdwood herself.

Jeanie and Marion Sapples, the washerwoman, with a pickle tea and sugartied in the corners of a napkin, and two measured glasses of whisky in anold doctor's bottle, had been sent with the foul clothes the night beforeto the washing-house, and by break of day they were up and at their work;nothing particular, as Marion said, was observed about Jeanie till afterthey had taken their breakfast, when, in spreading out the clothes on thegreen, some of the ne'er-do-weel young clerks of the town were seengaffawing and haverelling with Jeanie, the consequence of which was, thatall the rest of the day she was light-headed; indeed, as Mrs Girdwoodtold me herself, when Jeanie came in from the green for Marion's dinner,she couldna help remarking to her goodman, that there was something feyabout the lassie, or, to use her own words, there was a storm in hertail, light where it might. But little did she think it was to bring thedule it did to her.

Jeanie having gotten the pig with the wonted allowance of broth and beefin it for Marion, returned to the green, and while Marion was eating thesame, she disappeared. Once away, aye away; hilt or hair of Jeanie wasnot seen that night. Honest Marion Sapples worked like a Trojan to thegloaming, but the light latheron never came back; at last, seeing noother help for it, she got one of the other women at the washing-house togo to Mrs Girdwood and to let her know what had happened, and how thebest part of the washing would, unless help was sent, be obliged to lieout all night.

The deacon's wife well knew the great stake she had on that occasion inthe boyne, and was for a season demented with the thought; but at lastsummoning her three daughters, and borrowing our lass, and Mr Smeddum thetobacconist's niece, she went to the green, and got everything safelyhoused, yet still Jeanie Tirlet never made her appearance.

Mrs Girdwood and her daughters having returned home, in a most uneasystate of mind on the lassie's account, the deacon himself came over tome, to consult what he ought to do as the head of a family. But Iadvised him to wait till Jeanie cast up, which was the next morning.Where she had been, and who she was with, could never be delved out ofher; but the deacon brought her to the clerk's chamber, before BailieKittlewit, who was that day acting magistrate, and he sentenced her to bedismissed from her servitude with no more than the wage she had actuallyearned. The lassie was conscious of the ill turn she had played, andwould have submitted in modesty; but one of the writers' clerks, animpudent whipper-snapper, that had more to say with her than I need tosay, bade her protest and appeal against the interlocutor, which thedaring gipsy, so egged on, actually did, and the appeal next court daycame before me. Whereupon, I, knowing the outs and ins of the case,decerned that she should be fined five shillings to the poor of theparish, and ordained to go back to Mrs Girdwood's, and there stay out theterm of her servitude, or failing by refusal so to do, to be sent toprison, and put to hard labour for the remainder of the term.

Every body present, on hearing the circumstances, thought this a mostjudicious and lenient sentence; but so thought not the other

servantlasses of the town; for in the evening, as I was going home, thinking noharm, on passing the Cross-well, where a vast congregation of them wereassembled with their stoups discoursing the news of the day, they openedon me like a pack of hounds at a tod, and I verily believed they wouldhave mobbed me had I not made the best of my way home. My wife had beenat the window when the hobleshow began, and was just like to die ofdiversion at seeing me so set upon by the tinklers; and when I enteredthe dining-room she said, "Really, Mr Pawkie, ye're a gallant man, to beso weel in the good graces of the ladies." But although I have oftensince had many a good laugh at the sport, I was not overly pleased withMrs Pawkie at the time--particularly as the matter between the deacon'swife and Jeanie did not end with my interlocutor. For the latheron'sfriend in the court having discovered that I had not decerned she was todo any work to Mrs Girdwood, but only to stay out her term, advised herto do nothing when she went back but go to her bed, which she was bardyenough to do, until my poor friend, the deacon, in order to get a quietriddance of her, was glad to pay her full fee, and board wages for theremainder of her time. This was the same Jeanie Tirlet that wastransported for some misdemeanour, after making both Glasgow andEdinburgh owre het to hold her.

The Provost

The Provost Ringan Gilhaize, or, The Covenanters

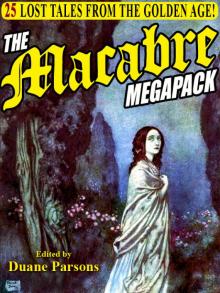

Ringan Gilhaize, or, The Covenanters The Macabre Megapack: 25 Lost Tales from the Golden Age

The Macabre Megapack: 25 Lost Tales from the Golden Age